Procurement

- US$3.3 billion

- worth of food bought from 101 countries in 2022

- US$1.2 billion

- worth of goods and services bought in 2022

Far from the traditional image of humanitarian agencies flying in food from far-off lands, the World Food Programme (WFP) sources more than 60 percent of its US$4.5 billion in supply chain costs for food, goods, and services in locations where we operate.

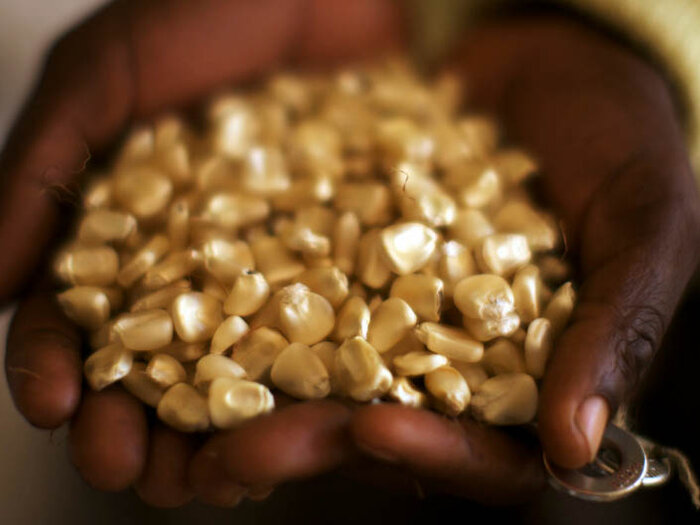

Whether it is sorghum in Mali and Sudan, maize meal in the Democratic Republic of Congo, or large transport contracts in Darfur, WFP “buys local”, or at least regional, wherever possible. As the largest purchaser of staple crops in Africa, WFP also increasingly purchases from smallholder farmers (US$71 million in 2022).

Even in the depth of crisis, we turn to local suppliers, thereby supporting local economies. In Syria, in spite of the conflict, we purchase 100% of the salt we need for our operations from national producers, whom we have helped raise quality to meet international procurement standards.

To fulfil its mandate to combat hunger, every year WFP buys more than 4 million metric tons of foodstuffs (4.2 million metric tons in 2022) – mainly cereals, pulses and specialized nutritious foods – for a value of over US$2 billion. For our cash-assistance operations, we purchase an annual value of US$3 billion in cash-based transfers, which is spent in local retail markets.